Plant Tweets, Part 2

This post is a follow-up to the one I wrote last month on how I got my plant

to tweet. That post covered the hardware

involved in getting my plant’s current thoughts as far as Linux running on my

Raspberry Pi. Today I’ll show you how I used Python to turn the output into

something I could use in code. Again, my goal is for this to be easy to follow even if you’ve never

built a project like this before, so please @ me

(@SaraBee) if you have questions.

This post is a follow-up to the one I wrote last month on how I got my plant

to tweet. That post covered the hardware

involved in getting my plant’s current thoughts as far as Linux running on my

Raspberry Pi. Today I’ll show you how I used Python to turn the output into

something I could use in code. Again, my goal is for this to be easy to follow even if you’ve never

built a project like this before, so please @ me

(@SaraBee) if you have questions.

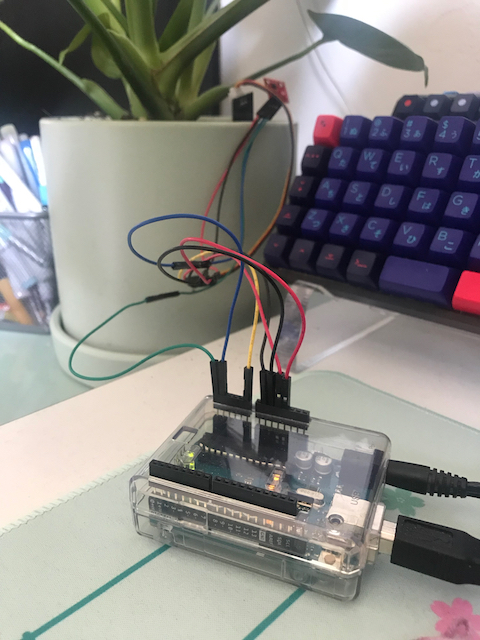

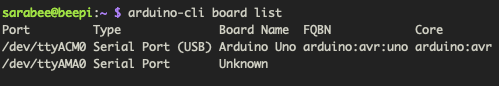

Last post, we had the Arduino hooked up to my plant’s sensor plugged into my Raspberry Pi via USB. First thing’s first: we

need to find the Arduino here in Linux land. Conveniently, Arduino has a set of command line tools called

arduino-cli. We can

look for any boards connected to the Raspberry Pi using the command

arduino-cli board list:

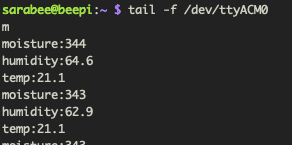

Cool, it’s in there, and now we know which port it’s hooked up to! Next, let’s listen in on what’s being sent from the Arduino. Because in Linux our serial ports are represented by files, we can watch the

latest data stream to the command line using tail -f /dev/ttyACM0:

You may notice that this output contains not just moisture levels but also

temperature and humidity; this is because I added a sensor since my last post.

Okay, great! Monstera, you’re coming through loud and clear. Now, how do we gain access to this data in code? I used this project to get more comfortable writing Python, and there’s a very straightforward Python library called PySerial that does exactly what we’re looking for. To grab some bytes off of our serial port buffer and print to the command line, our Python looks like this:

import serial

ser = serial.Serial('/dev/ttyACM0', 9600, timeout=1)

sample = ser.read(200) # pull 200 bytes off serial

print(sample)Our output is a bytes object that looks like:

b'\r\nmoisture:345\r\nhumidity:63.1\r\ntemp:21.1\r\np:21.1\r\nmoisture:345\r\nhumidity:60.9\r\ntemp:21.1\r\nmoisture:345\r\nhumidity:61.9\r\ntemp:21.1\r\nmoisture:345\r\nhumidity:63.1\r\ntemp:21.1\r\np:21.1\r\nmoisture:345\r\nhumidity'Cool cool. If you’re like me, you might be more comfortable manipulating strings than byte objects, so let’s decode it using utf-8 and turn it into a list of readings:

import serial

ser = serial.Serial('/dev/ttyACM0', 9600, timeout=1)

sample = ser.read(200) # pull 200 bytes off serial

sample_list = sample.decode('utf-8').split('\r\n')Rad. Now we’ve got a list of individual readings that each look something like

temp:21.1 or moisture:345. However, because we’re reading bytes off

a buffer, we might also sometimes get an incomplete reading that looks like moisture:3

or emp:21.1. In my actual implementation, I only split on newline (\n) and used the carriage return character (\r) to indicate that we were looking at the complete value for a reading before stripping it off. I could then split each reading again on the colon and place the pieces into keys and values in a dictionary:

import serial

ser = serial.Serial('/dev/ttyACM0', 9600, timeout=1)

sample = ser.read(200) # pull 200 bytes off serial

sample_list = sample.decode('utf-8').split('\n')

readings = {

"temp": [],

"humidity": [],

"moisture": []

}

for reading in sample_list:

if '\r' not in reading:

break

reading = reading.strip()

reading_kv = reading.split(':')

if len(reading) == 2:

key = reading[0]

val = reading[1]

if key == "moisture":

readings["moisture".append(int(val))

elif key in ["humidity", "temp"]:

readings[key].append(float(val))In my actual implementation I do a little bit more to ensure I succesfully was able to cast the values to ints or floats, but that’s basically it. I then have a dictionary where my keys are the different types of readings, and the values are lists of readings for each type.

Quick aside: you may notice that if you run a script like the above multiple

times in succession that subsequent runs may not receive a full sample (or

maybe nothing at all). When we call ser.read(200) we are asking the kernel

for 200 bytes; if the buffer has all 200 bytes, we’re all set, and then buffer

then gets flushed. The next time we call ser.read(200), maybe there isn’t

anything much in the buffer, so we get either 200 bytes or as much as can be

scraped together before the timeout we set when we instantiate Serial the line

above that. This behavior will all depend on how frequently you’re writing out data on

the Arduino side, your timeout, and how frequently you’re reading on the RPi

side. I am super curious about how reading from the buffer clears it

out, and while I haven’t yet found resources on exactly this topic I did find the Linux Serial HOWTO doc to be an interesting read.

At this point, we’ve successfully liberated our readings from the bytes streaming in over serial and turned them into something we can use in our code however we’d like. This feels like a good stopping point, but if you’re interested in the rest of the project and want to hear about how it uses thought catalogs to randomize the content of its tweets, how I wrote my Twitter API client, or how I used argparse and a couple of crons to tweet about moisture and humidity on different cadences, please let me know!